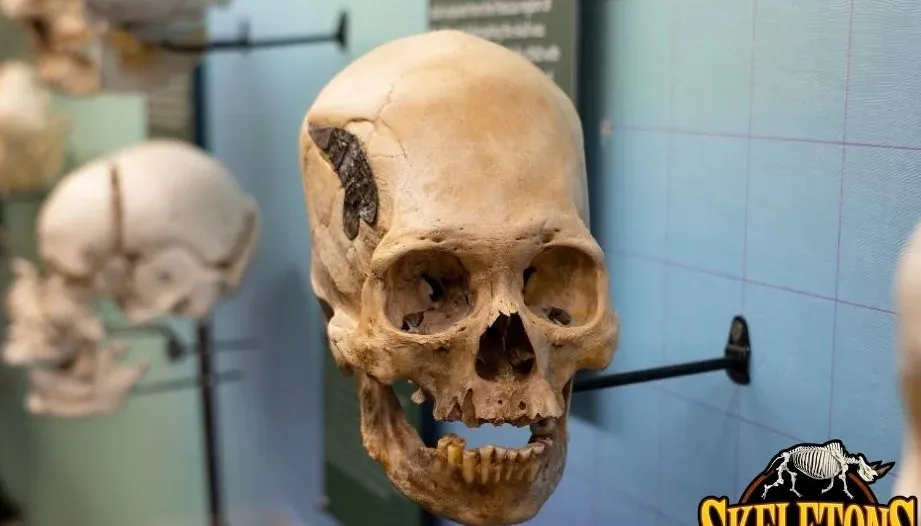

The Museum of Osteology in Oklahoma has revealed a fascinating archaeological find: a Peruvian warrior’s skull dating back 2,000 years, intricately fused with metal. This stands as one of the earliest instances of advanced surgery globally. Presumed to be the skull of a man wounded in combat, it underwent groundbreaking surgical procedures, featuring the implantation of a metal piece to heal the fracture.

Experts, as reported by the Daily Star, emphasize that the triumph of this ancient Peruvian surgery marks a pivotal revelation, shedding light on the advanced surgical prowess of ancient societies. The distinct skull under scrutiny is an example of Peruvian elongated skulls, providing insights into ancient body modification practices. This involved intentional skull deformation in tribal traditions, achieved through techniques like cloth binding or applying pressure between two pieces of wood over extended periods.

The Museum declared, ‘This Peruvian elongated skull, surgically implanted with metal after returning from battle, dates back approximately 2000 years. It stands out as one of our most captivating and ancient artifacts in the collection. While detailed information about this piece is limited, it is known that the individual survived the surgical procedure.’ The impeccably fused fractured bone encasing the repair serves as compelling evidence of the surgery’s success.

Originally part of the museum’s private collection, the skull gained heightened public interest, leading to its official exhibition in 2020. The artifact’s origin in Peru is significant, given the region’s historical association with adept surgeons who developed sophisticated techniques for treating skull fractures, prevalent injuries resulting from ancient battle weaponry like slingshots.

Elongated skulls were a common feature in ancient Peru, achieved through the intentional deformation of a person’s cranium, typically by binding it between two pieces of wood. Multiple theories attempt to explain the practice of skull elongation, including the possibility of societal elites using it as a distinctive marker or as a form of defensive cultural tradition. Subsequent archaeological discoveries have indicated that Peruvian women with elongated skulls experienced a reduced susceptibility to severe head injuries compared to those without such modifications.