In 1909, a New York businessman named Samuel Brown traveled to Egypt to purchase a pair of ancient mummies for the Institute of History and Art in Albany, where he served as a board member. Brown and subsequent generations of researchers believed that he had brought home a female mummy dating back to the 21st Dynasty and a male mummy from the Ptolemaic period.

But when the Egyptologist from Emory Uniʋersity, Peter Lacovara, visited the institute in the early 2000s, he sensed that the female mummy was not in the coffin where she was originally buried. Perhaps it wasn’t a female mummy at all.

Up and Up: Unraveling the Mummy of Ankhefenmut from the XXI Dynasty (1069-945 B.C.) discovered in Bab el-Gasus, Egypt. Historians originally believed Ankhefenmut to be a woman. > Image Credit: Institute of History and Art, Albany. Gift of Samuel Brown, 1909

Up and Up: Unraveling the Mummy of Ankhefenmut from the XXI Dynasty (1069-945 B.C.) discovered in Bab el-Gasus, Egypt. Historians originally believed Ankhefenmut to be a woman. > Image Credit: Institute of History and Art, Albany. Gift of Samuel Brown, 1909

Lacovara knew that other museums had made mistakes in “sexing mummies,” so he proposed scanning the remains with GE computed tomography (CT) and X-ray equipment at the Albany Medical Center.

The tests confirmed his hunch. The 3,000-year-old “female” mummy had a masculine pelvis and thicker, more angular male bones. The team also noted that the upper right side of the mummy’s body was “decidedly more muscular.”

This, combined with marks on the coffin, led investigators to conclude that the mummy was Ankhefenmut, a priest and sculptor from the Temple of Mut near Luxor, who lived between 1069 and 945 B.C.

Egyptologist Peter Lacovara (center) studied Ankhefenmut on a GE-manufactured CT scanner. Image Credit: GE Healthcare

Egyptologist Peter Lacovara (center) studied Ankhefenmut on a GE-manufactured CT scanner. Image Credit: GE Healthcare

Such are the wonders of modern medical technology that scanners revealed other treasures. Researchers found that the mummy’s bones were “well mineralized, solid, and uniform,” indicating that Ankhefenmut’s diet “contained adequate proteins and calcium.” And “his dentition was exceptional, with no cavities or tooth loss.” He was about 50 years old when he died.

In 2013, the Albany Institute invited Lacovara to curate an exhibition that corrected the history of their mummies. The exhibition, “GE Presents: The Mystery of the Albany Mummies,” opened a year later.

This wasn’t the first time GE’s medical technology helped historians explore the past. In 2011, anthropologists from the Milwaukee Public Museum scanned mummies from Peru and Egypt, including the head of an Egyptian named Djedhor.

Djedhor was first scanned in 1986. But in 2006, newer technology revealed a hole in his skull, leading anthropologists to conclude that he had undergone a primitive form of brain surgery.

“We’ve been doing this for 25 years with GE,” said Carter Lupton, head of anthropology at the Milwaukee museum. “Every time we go out, it’s a different generation of technology, better images, better information, better ways, and it’s also faster.

GE has been helping historians scan and identify mummies since 1939. Back then, GE’s medical scanners produced X-ray images of mummies for the New York World’s Fair (above). Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.

GE has been helping historians scan and identify mummies since 1939. Back then, GE’s medical scanners produced X-ray images of mummies for the New York World’s Fair (above). Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.

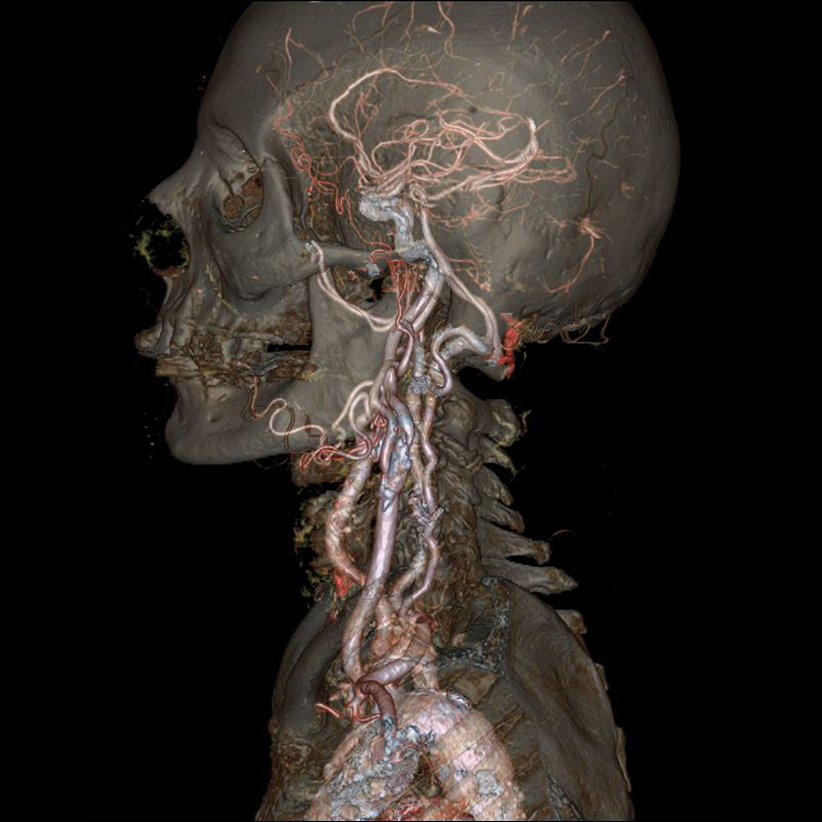

CT scanners produce detailed images of the human body. The latest imaging systems, such as GE’s Revolution CT, provide impressive images of organs, bones, blood vessels, and other parts of the body. Image credit: GE Healthcare.

CT scanners produce detailed images of the human body. The latest imaging systems, such as GE’s Revolution CT, provide impressive images of organs, bones, blood vessels, and other parts of the body. Image credit: GE Healthcare.